On a quiet January morning in Carillo Farm, Bingawan, Iloilo, something small but quietly radical happened. Eighteen people—farm staff, community members, barangay leaders, and development workers—gathered not for a ceremony or a speech-heavy program, but to learn how to make liniment. By day’s end, they would produce seventy-five bottles of PaumPAU Liniment. More importantly, they would leave with something harder to bottle: confidence.

The activity began, as many meaningful community gatherings do, with a prayer—grounding everyone in intention. From there, Ms. Concepcion Carillo of CFARM led an orientation that felt less like a lecture and more like a conversation shaped by years of lived experience. She spoke about Carillo Farm’s journey from a modest livelihood effort into an ATI-accredited training institution, quietly reminding the group that credibility is built slowly, with consistency and care.

“This didn’t start big,” she shared candidly, explaining how livelihood, when rooted in local realities, grows not by shortcuts but by trust. She introduced participants to CFARM’s training programs, many of which lead to NC II certifications—pathways not only to employment but to entrepreneurship. The message was clear: skills are portable, dignified, and powerful.

The discussion on essential oils and liniment production followed, anchored in a simple but often overlooked principle—use what the community already has. Local herbal plants, readily available in the barangay, were presented not as alternatives but as assets. Sustainable. Affordable. Familiar. In a world chasing imported solutions, the session gently argued for the wisdom growing in one’s own backyard.

The most stirring moment came not from a slide deck but from a story. Ms. Queenie Carillo-Biag, daughter of Ms. Carillo, stood before the group and spoke of beginnings marked by uncertainty. Their family, she said, started from scratch—armed more with grit than resources. Life was not kind or linear, but it was instructive.

“The burdens you carry are temporary,” she told the participants, her words landing softly but firmly. She urged them not to remember faces or names, but the skills they would take home. “Those,” she implied, “are what will stay with you.”

Then came the work.

Hands-on, deliberate, and communal, the liniment-making process unfolded step by step: selecting herbs, preparing and extracting them through controlled cooking, mixing formulations with precision. Safety and hygiene were emphasized, not as rigid rules but as respect—for the product and the people who would eventually use it.

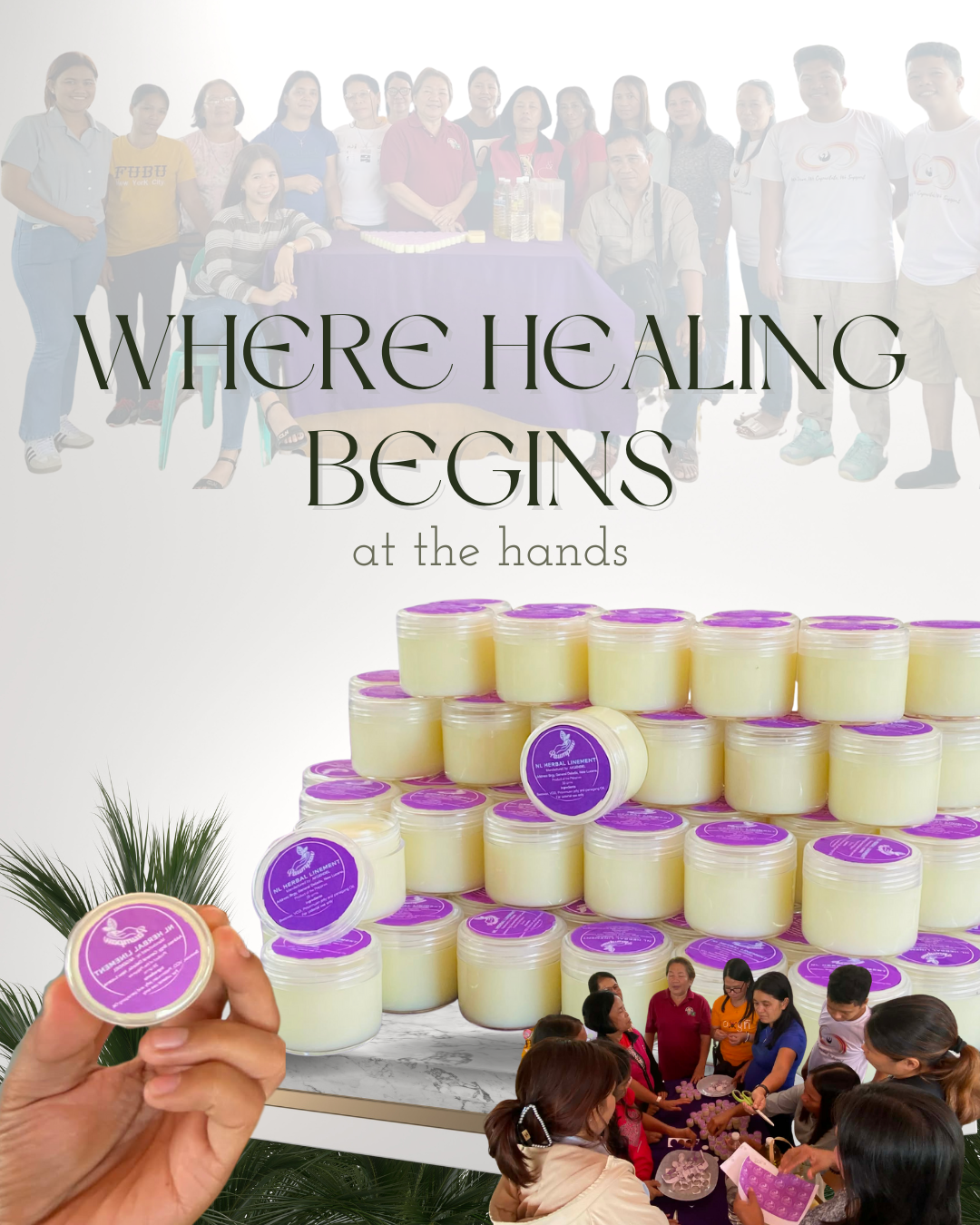

Participants moved easily between roles: measuring, stirring, bottling, labeling. SEA staff and AKGENDEL members worked alongside farm staff, blurring distinctions between trainer and trainee. During packaging, creativity took center stage as ideas flew about labels, colors, and branding. PaumPAU Liniment emerged not just as a product, but as a shared creation.

Barangay support was visible and tangible. Punong Barangay Francisco Silubrico Jr. of Barangay General Delgado was present throughout, signaling that livelihood development is not a side project but a governance priority. The women of General Delgado echoed this support, expressing appreciation and a clear intention to begin herbal planting initiatives—ensuring that future production would be rooted, literally, in their own soil.

Notably, Ms. Concepcion Carillo pushed through the day despite feeling unwell. It was a quiet act of dedication that did not go unnoticed. Her presence underscored a truth many in the room already knew: community work is sustained not by convenience, but by commitment.

By the end of the training, the numbers were impressive—eighteen participants, seventy-five liniments produced. But the real outcome was less quantifiable. There was a renewed sense of possibility, a growing awareness that livelihood does not always require leaving one’s community, and a shared belief that small skills, when nurtured collectively, can grow into enterprises.

In Bingawan that day, liniment-making became more than a technical exercise. It was a lesson in resilience, local wisdom, and collaboration. Healing, it turned out, did not only come from the bottle—but from the process of making it together.

Leave a Reply